archival context on the web

On Mark’s advice I attended the Moving Forward With Authority Society of American Archivists pre-conference, which focused on the role of authority control in archival descriptions. There were lots of presentations/discussions over the day, but by and large most of them revolved around the recent release of the Encoded Archival Context: Corporate Bodies, Persons and Families (EAC-CPF) XML schema. Work on the EAC-CPF began in 2001 with the Toronto Tenets, which articulated the need for encoding not only the contents of archival finding aids (w/ Encoded Archival Description), but also the context (people, families, organizations) that the finding aid referenced:

Archival context information consists of information describing the circumstances under which records (defined broadly here to include personal papers and records of organizations) have been created and used. This context includes the identification and characteristics of the persons, organizations, and families who have been the creators, users, or subjects of records, as well as the relationships amongst them.

Toronto Tenets

I’ll admit I’m jaded. So much XML has gone under the bridge, that it’s hard for me to get terribly excited (anymore) about yet-another-xml-schema. Yes, structured data is good. Yes, encouraging people make their data available similarly is important. But for me to get hooked I need a story for how this structured data is going to live, and be used on the Web. This is the main reason I found Daniel Pitti’s talk about the Social Networks of Archival Context (SNAC) to be so exciting.

SNAC is an NEH (and possibly IMLS soon) funded project of the University of Virginia, California Digital Library, and the Berkeley School for Information. The project’s general goal is to:

… unlock descriptions of people from descriptions of their records and link them together in exciting new ways.

Where “descriptions of their records” are EAD XML documents, and “linking them together” means exposing the entities buried in finding aids (people, organizations, etc), assigning identifiers to them, and linking them together on the web. I guess I might be reading what I want a bit into the goal based on the presentation, and my interest in Linked Data. If you are interested, more accurate information about the project can be found in the NEH Proposal that this quote came from.

Even though SNAC was only very recently funded, Daniel was already able to demonstrate a prototype application that he and Brian Tingle worked on. If I’m remembering this right, Daniel basically got a hold of the EAD finding aids from the Library of Congress, extracted contextual information (people, families, corporate names) from relevant EAD elements, and serialized these facts as EAC-CPF documents. Brian then imported the documents using an extension to the eXtensible Text Framwork, which allowed XTF to be EAC-CPF aware.

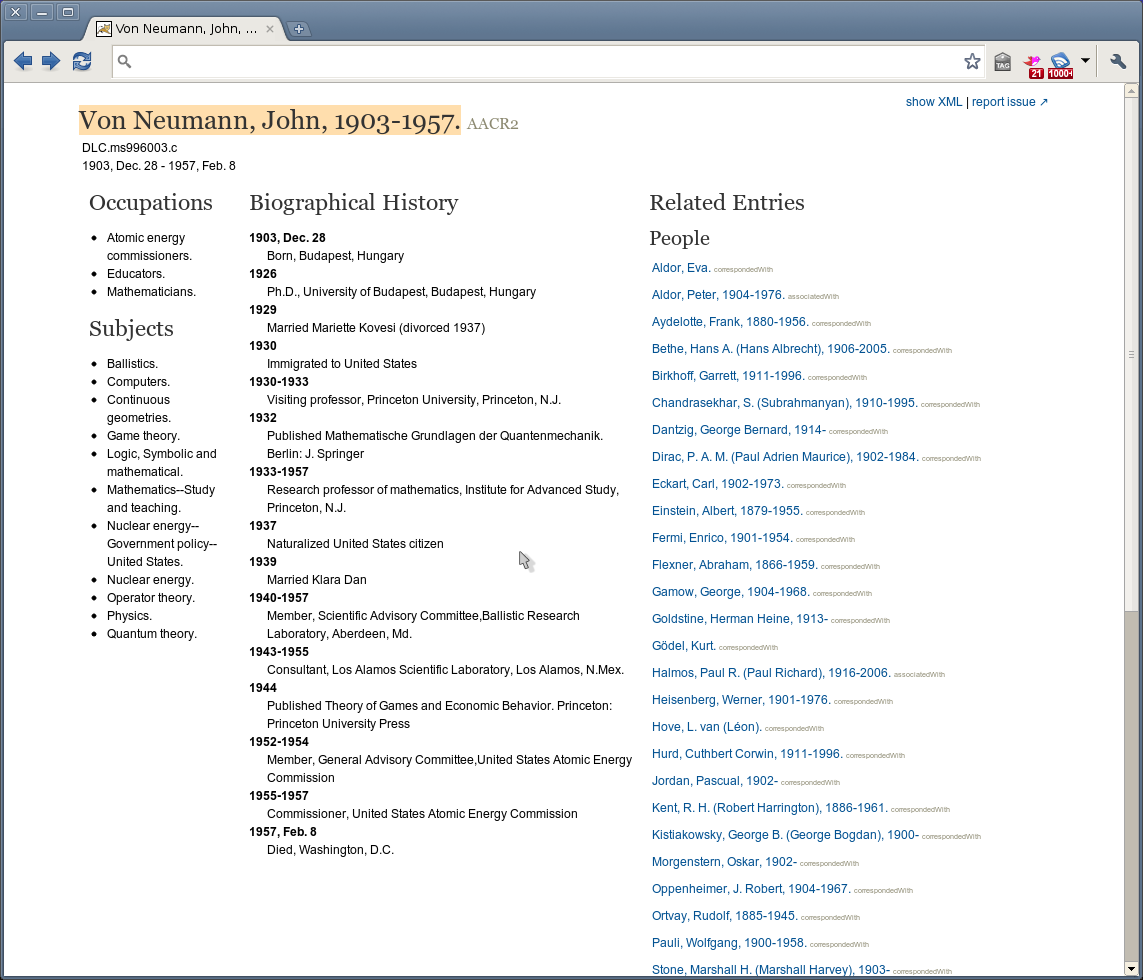

The end result is a web application that lets you view distinct web pages for individuals mentioned in the archival material. For example here’s one for John von Neumann

All those names in the list on the right are themselves hyperlinks which take you to that person’s page. If you were able to scroll down (the prototype hasn’t been formally launched yet) you could see links to corporate names like Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, The Institute for Advanced Study, US Atomic Energy Commission, etc. You would also see a Resources section that lists related finding aids and books, such as the John von Neumann Papers finding aid at the Library of Congress.

I don’t think I was the only one in the audience to immediately see the utility of this. In fact it is territory well trodden by OCLC and the other libraries involved in the VIAF project which essentially creates web pages for authority records for people like John Von Neumann who have written books. It’s also similar to what People Australia, BibApp and VIVO are doing to establish richly linked public pages for people. As Daniel pointed out: archives, libraries and museums do a lot of things differently; but ultimately they all have a deep and abiding interest in the intellectual output, and artifacts created by people. So maybe this is an area where we can see more collaboration across the cultural divides between cultural heritage institutions. The activity of putting EAD documents, and their transformed HTML cousins on the web is important. But for them to be more useful they need to be contextualized in the web itself using applications like this SNAC prototype.

I immediately found myself wondering if the URL say for this SNAC view of John von Neumann could be considered an identifier for the EAC-CPF record. And what if the HTML contained the structured EAC-CPF data using xml+xslt, a microformat, rdfa or a link rel pointing at an external XML document? Notice I said an instead of the identifier. If something like EAC-CPF is going to catch on lots of archives would need to start generating (and publishing) them. Inevitably there would be duplication: e.g. multiple institutions with their own notion of John von Neumann. I think this would be a good problem to have, and that having web resolvable identifiers for these records would allow them to be knitted together. It would also allow hubs of EAC-CPF to bubble up, rather than requiring some single institution to serve as the master database (as in the case of VIAF).

A few things that would be nice to see for EAC-CPF would be:

- Instructions on how to link EAD documents to EAC-CPF documents.

- Recommendations on how to make EAC-CPF data available on the Web.

- A wikipage or some low-cost page for letting people share where they are publishing EAC-CPF.

In addition I think it would be cool to see:

- A microformat for making EAC-CPF data available in HTML. If not an official Microformat then Plain Old Semantic HTML will do. It might also be possible to leverage some existing Microformats like hCard.

- A EAC-CPF RDF schema for embedding EAC-CPF data in HTML using RDFa and other Linked Data environments. Heck, Facebook is doing it. It might also be useful to leverage existing vocabularies like <a href=’’http://xmlns.com/foaf/spec/“>FOAF, Organization Ontology, etc using a Dublin Core Application Profile.

Anyhow I just wanted to take a moment to say how exciting it is to see the stuff hiding in finding aids making it out onto the Web, with URLs for resources like People, Corporations and Families. I hope to see more as the SNAC project integrates more with existing name authority files (work that Ray Larson at Berkeley is going to be doing), and importing finding aids from more institutions with different EAD encoding practices.