Baltimore Stories

I’m in Baltimore today to participate in a public event in the Baltimore Stories series sponsored by the University of Maryland and the Maryland Humanities Council with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Check out the #bmorestories hashtag and the schedule for information about other events in the series. I’m particularly honored and excited to take part because of MITH’s work in build a research archive of tweets related to the protests in Baltimore last year, and a little bit of collaboration with Denise Meringolo and Joe Tropea to connect their BaltimoreUprising archive with Twitter. And of course there is my involvement in the Documenting the Now project, where the role of narrative and its place in public history is so key.

Since it’s a public event I’m not really sure who is going to show up tonight. The event isn’t about talking heads and powerpoints. It’s an opportunity to build conversations about the role of narrative in community and cultural/historical production. This blog post isn’t the text of a presentation, it’s just a way for me to organize some thoughts and itemize a few things about narrative construction in social media that I hope to have a chance talk about with others who show up.

Voice

To give you a little bit more of an idea about what Baltimore Stories is aiming to do here’s a quote from ther NEH proposal:

The work we propose for this project will capitalize on the public awareness and use of the humanities by bringing humanities scholars and practitioners into conversation with the public on questions that are so present in the hearts and minds of Baltimoreans today: Who are we, Baltimore? Who owns our story? Who tells our stories? What stories have been left out? How can we change the narrative? We imagine the exploration of narratives to be of particular interest to Baltimore, and to other cities and communities affected by violence and by singular narratives that perpetuate violence and impede understanding and cooperation. We believe that the levels of transdisciplinarity and collaboration with public organizations in this project are unprecedented in a city-wide collaboration of the humanities and communities.

In one of the previous Baltimore Stories events, film maker and multi-media artist Ralph Crowder talked about his work documenting the events in Ferguson Missouri last year. I was particularly struck by his ability to connect with the experience of the highschool students in the audience and relate it to his work as an artist. One part of this conversation really stuck with me:

Don’t ever be in a situation where you feel like you don’t have a voice. Don’t ever be in a situation where someone else is talking for your experience. You be the person who does that for you. Because if you can’t do that someone else is going to come around and they’re going to talk for what you are going through, and many times they are going to get paid some money off of your struggle.

As someone that received a grant from a large foundation to help build tools and community around social media archiving and events like those in Ferguson, Missouri and those in Baltimore I can’t help but feel implicated by these words–and to recognize their truth. I grew up in the middle class suburbs of New Jersey, where I was raised by both my Mom or Dad. I shouldn’t have been, but I was shocked by how many kids raised their hands when Crowder asked how many were being raised by only one parent, and how many were being raised by no parent at all. I know I am coming from a position of privilege, and that that the mechanics of this privilege afford yet more privilege. But getting past myself for a moment I can see what Crowder is saying here is important. What he is saying is in fact fundamental to the work we are doing on Documenting the Now, and the value proposition of the World Wide Web itself.

For all its breathless techno solutionist promises and landscape fraught with abuse and oppression, social media undeniably expands individuals’ ability to tell their own stories in their own voice to a (potentially) world wide audience. This expansion is of course relative to individual’s ability to speak to that same audience in earlier mediums like letters, books, magazines, journals, television and radio. The Web itself made it much easier to publish information to a large audience. But really the ability to turn the crank of Web publishing was initially limited to people with a very narrow set of technical skills. What social media did was greatly expand the number of people who could publish on the Web, and share their voices with each other, and with the world.

Stories

The various social media platforms (Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Google+, Facebook, Tumblr, etc) condition what can be said, who it can be said to, and who can say things back. This is an incredibly deep topic that people have written books about. But to get back to Crowder’s advice, consider the examples of DeRay McKesson, Devin Allen, Johnetta Elzie, Alicia Garza and countless others who used social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to document the BlackLivesMatter movement, and raise awareness about institutionalized racism. Checkout DeRay’s Ferguson Beginnings where he has been curating his own tweets from Ferguson in 2014. Would people like me know about Ferguson and BlackLivesMatter if people like DeRay, Devin, Johnetta and Alicia weren’t using social media to document their experience?

It’s not my place to tell this story. But as someone who studies the Web, builds things for the Web here are a few things to consider when deciding how to and where to tell your story on the Web.

Hashtags

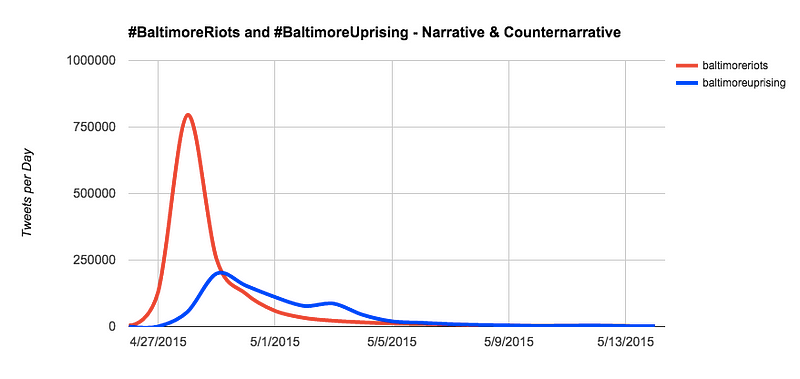

Hashtags matter. Bergis and I saw this when we were collecting the #BaltimoreRiots and #BaltimoreUprising tweets. We saw the narrative tension between the two hashtags, and the attempts to reframe the protests that were going on here in Baltimore.

Take a look at a sampling of random tweets with media using the #BaltimoreRiots and #BaltimoreUprising. Do you get a sense of how they are being used differently? #BlackLivesMatter itself is emblematic of the power of naming in social media. Choosing a hashtag is choosing your audience.

Visibility

When you post to a social media platform be aware of who gets to see it and the trade offs associated with that decision. For example, by default when you publish a tweet you are publishing a message for the world. Only people who follow you get an update about it. But anyone in the world can see it if they have the URL for your tweet. You can delete a tweet which will remove the tweet from the Web, but it won’t pull it back from the clients and other places that may have stored it. You can choose to make your account protected which means it is only viewable by people you grant access to. The different social media platforms have different controls for who gets to see your content. Try to understand the controls that are available. When you share things publicly they obviously can be seen by a wider audience which gives it more reach. But publishing publicly also means your content will be seen by all sorts of actors, which may have other ramifications.

Surveillance

One of the ramifications is that social media is being watched by all sorts of actors, including law enforcement. We know from Edward Snowden and Glenn Greenwald that the National Security Agency is collecting social media content. The full dimensions of this work is hidden, but just google for police Facebook evidence or read this Wikipedia article and you’ll find lots of stories of how local law enforcement are using social media. Even if you aren’t doing anything wrong be aware of how your content might be used by these actors. It can be difficult but don’t let this surveillance activity have a chilling effect on you using exercising your right to freedom of speech, and using your voice to tell your story.

Harassment

When you publish your content publicly on the Web you open yourself up to harassment from individuals who may disagree with you. For someone like DeRay and many other public figures on social media this can mean having to block thousands of users because some of them send death threats and other offensive material. This is no joke. Learn how to leverage your social media tools to ignore or avoid these actors. Learn strategies for working with this content. Perhaps you want to have a friend look at your messages for you, to get some distance. Perhaps you can experiment with BlockBots and other collaborative ways of ignoring bad actors on the Web. If there are controls reporting spammers and haters use them.

Ownership

If you look closely at the Terms of Service for major social media platforms like Twitter, Instagram and Facebook you will notice that they very clearly state that you are the owner of the content you put on there. You also often grant the social media platform a right to redistribute and share that content as well. But ultimately it is yours. You can take your content and put it in multiple platforms such as YouTube, Vine and Facebook. You may want to use a site like Wikimedia Commons or Flickr that allow you to attach a Creative Commons license to your work. Creative Commons provides a set of licenses that let you define how your content can be shared on the Web. If you are using a social media platform like Tumblr that lets you change the layout of the website you can add a creative commons license to your site. Ultimately this is the advantage of creating a blog on Wordpress, Medium or hosting it yourself since you can claim copyright and license your material as you see fit. However it is a trade off since it may be more difficult to get the exposure that you will see in platforms like Instagram, Vine or Facebook. If you want you could give low resolution versions to social media outlets with links to high resolution versions you publish yourself with your own license.

Archive

Many social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Medium Instagram allow you to download an archive of all the content you’ve put there. When you are selecting a social media platform make sure you can see how to get your content out again. This could be useful if you decide to terminate your account for whatever reason, but retain a record of your work. Perhaps you want to move your content to another social media platform. Or perhaps you are creating a backup in case the platform goes away. Maybe, just maybe, you are donating your work to a local library or archive. Being able to download your content is key.