Static-Dynamic

At work we’ve been moving lots of previously dynamic web sites over to being static sites. Many of these sites have been Wordpress, Omeka or custom sites for projects that are no longer active, but which retain value as a record of the research. This effort has been the work of many hands, and has largely been driven (at least from my perspective) by an urge to make the websites less dependent on resources like databases, and custom code to render content. But we are certainly not alone in seeing the value of static site technology, especially in humanities scholarship.

The underlying idea here is that a static site makes the content more resilient, or less prone to failure over time, because there are less moving pieces involved in keeping it both on and of the web. The pieces that are moving are tried-and-true software like web browsers and web servers, instead of pieces of software that have had less eyes on them (my code). The web has changed a lot over its lifetime, but the standards and software of the web have stayed remarkably backwards compatible (Rosenthal, 2010). There is long term value in mainstreaming your web publishing practices and investing in these foundational technologies and standards.

Since they have less moving pieces static site architectures are also (in theory) more efficient. There is a hope that static sites lower the computational resources needed to keep your content on the web, which is good for the pocketbook and, more importantly, good for the environment. While there have been interesting experiments like this static site driven by solar energy it would be good to get some measurements on how significant these changes are. As I will discuss here in this post, I think static site technology can often push dynamic processing out of the picture frame, where it is less open to measurement.

Migrating completed projects to static sites has been fairly uncontroversial when the project is no longer being added to or altered. Site owners have been amenable to the transformation, especially when we tell them that this will help ensure that their content stays online in a meaningful and useful way. It’s often important to explain that “static” doesn’t mean their website will be rendered as an image or a PDF, or that the links won’t be navigable. Sometimes we’ve needed to negotiate the disabling of a search box. But it usually has sufficed to show how much the search is used (server logs are handy for this), and to point out that most people search for things elsewhere (e.g Google) and arrive at their website. So it has been a price worth paying. But I think this may say more about the nature of the projects we were curating, than it does about web content in general. YMMV. Cue the “There are no silver bullets” soundtrack. Hmm, what would that soundtrack sound like? Continuing on…

For ongoing projects where the content is changing, we’ve also been trying to use static site technology. Understandably there is a bit of an impedance mismatch between static site technology and dynamic curation of content. If the curators are comfortable with things like editing Markdown and doing Git commits/pushes things can go well. But if people aren’t invested in learning those things there is a danger that making a site static can well, make it too static, which can have significant consequences for an active project that uses the web as a canvas.

One way of adjusting for this is to make the static site more dynamic. It’s ok if you lol here. This tacking back can be achieved in a multitude of ways, but they mostly boil down to:

- Curating content in another dynamic platform and having an export of that data integrated statically into the website at build time (not at runtime).

- Curating content in another dynamic platform and including it at runtime in your web application using the platform’s API. For example think of how Google Maps is embedded in a webpage.

The advantage to #1 is that the curation platform can go away, and you still have your site, and your data, and are able to build it. But the disadvantage is that curatorial changes to the data do not get reflected in the website until the next build.

The advantage to #2 is that you don’t need to manage the data assets, and changes made in the platform are immediately available in the web application. But the downside is that your website is totally dependent on this external platform. The platform could choose to change their API, put the service behind a paywall, shut down the service or completely go out of business. Actually, it is a certainty that one of these will eventually happen. So, depending on the specifics, this kind of static site is arguably more vulnerable than the previous dynamic web application.

We’ve mostly been focused on scenario #1 in our recent work creating static sites for dynamic projects. For example we’ve been getting some good use of of Airtable as a content curation platform in conjunction with Gatsby and its gatsby-source-airtable plugin, which makes the Airtable data available via a GraphQL query that gets run at build time. Once built the pages have the data cooked into them, so Airtable can go away and our site will be fine. But the build is still quite dependent on Airtable.

In the (soon to be released) Unlocking the Airwaves project we also are using Airtable but we didn’t use the GraphQL plugin, mostly because I didn’t know about it at the time. On that project there is a fetch-data utility that will talk to our Airtable base and persist the data into the Git reposistory as JSON files. These JSON files are then queried as part of the build process. This means the build is insulated from changes in Airtable, and that you can choose when to pull the latest Airtable data down.

But the big downside to this approach is that when curators make changes in Airtable they want to see them reflected in the website quickly. They understandably don’t want to have to ask someone else for a build, or figure out how to build and push the site themselves. They just want their work to be available to others.

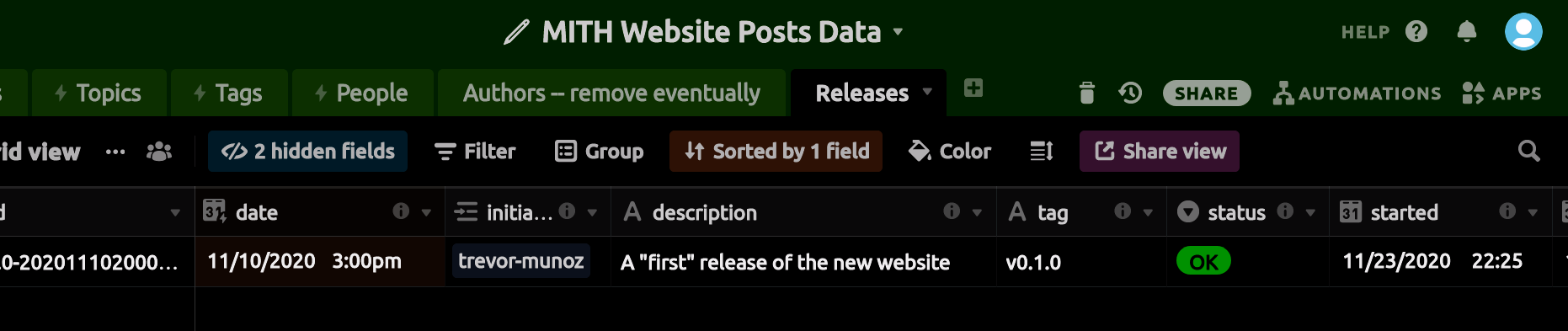

One stopgap between 1 and 2 that we’ve developed recently is to create a special table in Airtable called Releases. A curator can add a row with their name, a description, and a tagged version of the site to use, which will cause a build of the website to be deployed.

We have a program that runs from cron every few minutes and looks at this table and then decides whether a build of the site is needed. It is still early days so I’m not sure how well this approach will work in practice. It took a little bit of head scratching to come up with an initial solution where the release program uses this Airtable row as a lock to prevent multiple deploy processes from starting at the same time. Experience will show if we got this right. Let me know if you are interested in the details.

But stepping back a moment I think it’s interesting how static site web technology simultaneously creates a site of static content, while also pushing dynamic processing outwards into other places like this little Airtable Releases table, or one of the many so called Jamstack service providers. This is where the legibility of the processing gets lost, and it becomes even more difficult to ascertain the environmental impact of the architectural shift. What is the environmental impact of our use of NetlifyCMS or Airtable? It’s almost impossible to say, whereas before when we were running all the pieces ourselves it was conceiveable that we could audit them. These platforms are also sites of extraction as well, where it’s difficult to even know what economies our data are even participating in.

This is all to say that understanding the motivations to go static are complicated, and more work could be done to strategically think through some of these design decisions in a repeatable and generative way.